In March, the Letters of Note Instagram posted an excerpt of a letter written by Georgia O’Keeffe in 1933: “I have done nothing all summer but wait for myself to be myself again.” And all summer, I came across these words—shared directly from the account, from other accounts, typeset in different fonts across different backgrounds. Today, the Letters of Note post has more than 18,000 likes.

The excerpt requires no context to understand, to feel, to relate to. And the post’s comments form a resounding chorus: Same. A few examples of comments: “An ode to seasonal depression,” “Waiting for HRT to kick in,” and “Is this real? Because, if so, I feel much better about myself.”

It’s real. And, of all the things you could show to the ghost of Georgia O’Keeffe—who died in 1986 at the age of 98, before computers and cell phones could summon the private musings of a dead woman to your fingertips—her literary meme-ification might be one of the most surprising (as fools, fascism, and plague in their many forms are hardly recent apparitions).

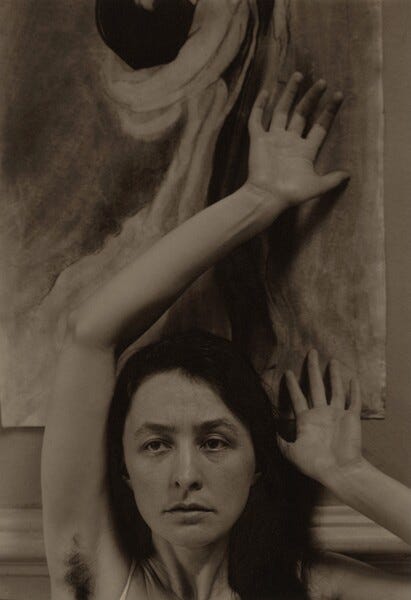

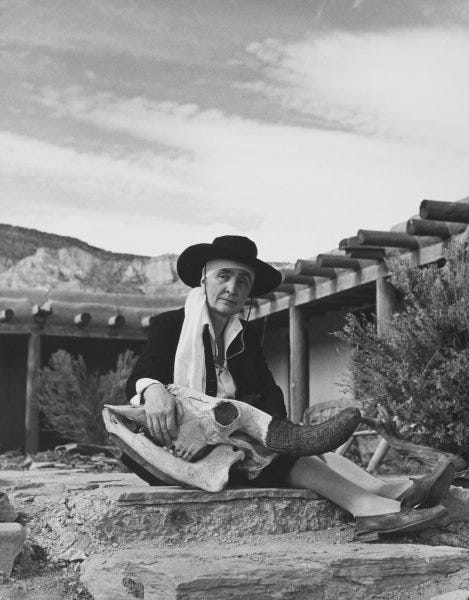

By the end of her life, Georgia certainly understood her celebrity and the power of possessing not only a public image but the means to influence it—working it carefully in her hands to shape it with the same intent and intensity as her art. Her work had found critical and financial success since the 1920s; and as she was establishing herself publicly with her painting, her likeness—including her nude body—had just as quickly been photographed, exhibited, and capitalized upon by her husband, Alfred Stieglitz (often lauded as one of the fathers of modern photography). In the wake of his death, she left New York and moved fully to New Mexico in 1949, where she would again be perennially photographed throughout the next four decades—by the likes of Ansel Adams, John Loengard, Bruce Weber, Tony Vaccaro, and Annie Leibovitz—but this time, in service of her own vision.

As exhibits like the Brooklyn Museum’s Living Modern in 2017 have more explicitly framed, Georgia participated in her own mythmaking.1 The Georgia O’Keeffe you know today, if you know (of) her, is at the very least descended from the identity she crafted for public consumption. Perhaps you have encountered one of these potted varieties: Georgia O’Keeffe, the self-reliant pioneer, the self-made woman, a “hard” and “straight shooter,” “angelic rattlesnake” of the high desert,2 master of modern simplicity in house and garment, form and function.

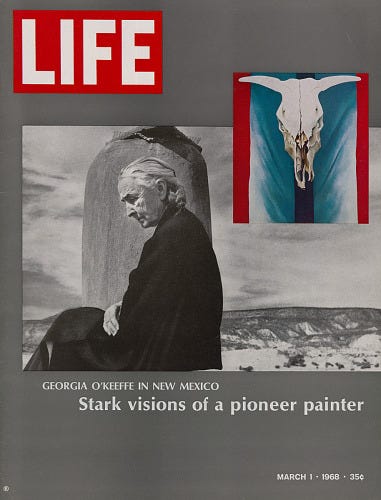

The photographs helped, capturing the artist alone in her homes (as she owned two by 1945, one in the village of Abiquiú and one twelve miles north at Ghost Ranch), against seemingly empty landscapes, along the crests of sweeping hills and wide, open skies.

The photographs accompanied interviews and headlines: “Stark visions of a pioneer painter,” ran LIFE Magazine in its first edition of March 1968. It’s easy to imagine Joan Didion responding to this cover story, penning Georgia an “angelic rattlesnake,” in her eponymous 1976 essay on the artist, later published in The White Album.

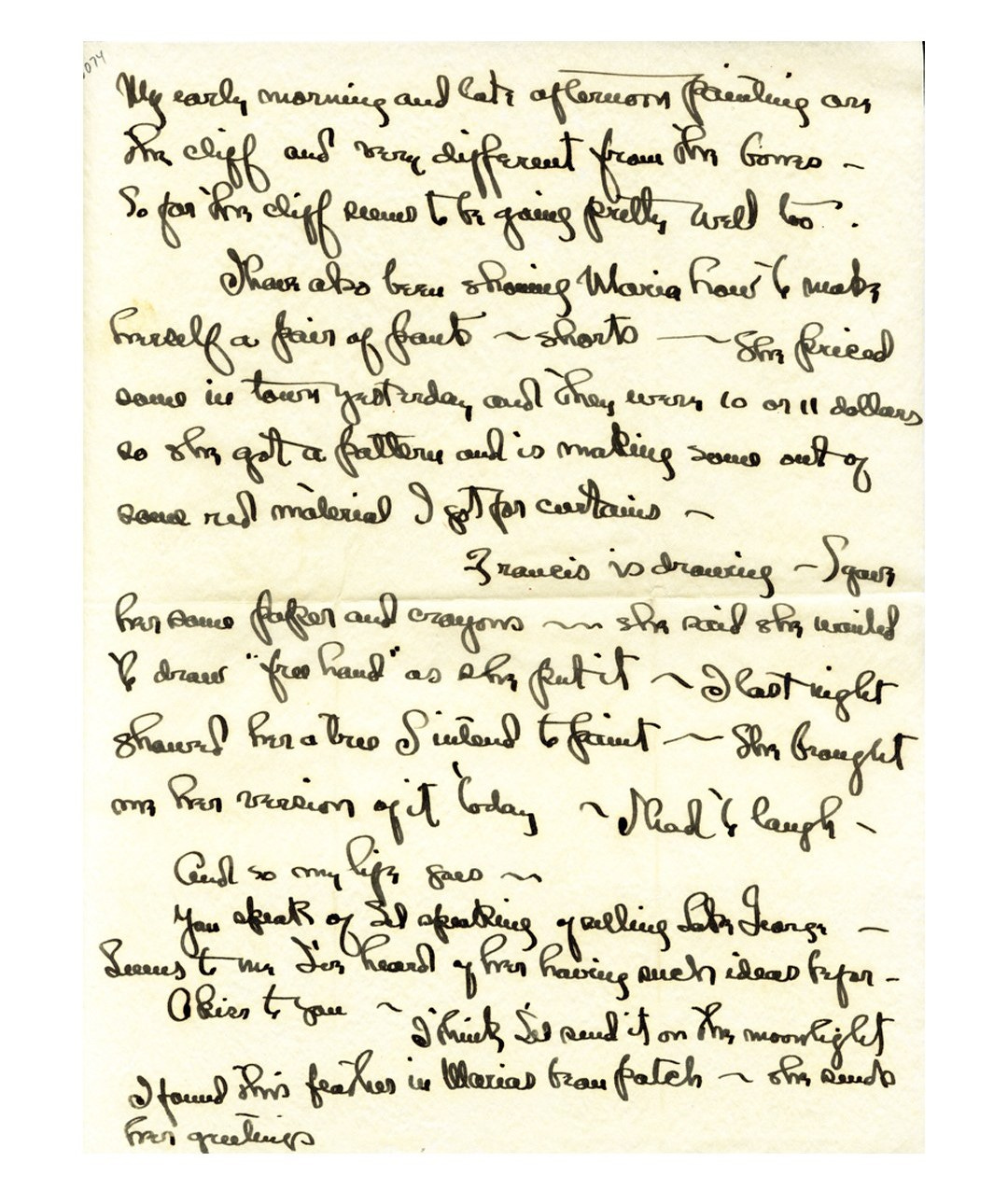

Georgia was far warier of words than photographs—of images of all kinds, shapes, forms, and colors. As a visual artist, she’d had to acquiesce to some extent to a one-way dialogue, mostly from male critics, in response to her work. But she knew all too well that her life would become an archive as Alfred’s had. Alfred was a prolific photographer, patron, and collector as well as correspondent—penning dispatches as long as forty pages and saving thousands of the letters he received.3 (He and Georgia exchanged more than 25,000 pages of letters between themselves.) More than twenty years Georgia’s senior, he left behind a gargantuan legacy and estate to settle, which she herself did—uncomfortably, alongside his much much younger lover4—for a grueling three years after his death.

As the years waned, Georgia prepared for this inevitability, even suggesting the eventual publication of her correspondence, though requiring much of it remain sealed until 20 years after her death.5 In the last odd decade of her life, she also undertook rare, welcome projects that granted unprecedented access—but in her own words. Some Memories of Drawings, containing a selection of both art and written reflections, she published in 1974; in a similar vein, the far more extensive Georgia O’Keeffe was published in 1976. It was this latter edition that Didion responded to, quite directly, in her essay: Georgia, at 90, in her own words. And Georgia had a bone to pick, with words in particular. Georgia O’Keeffe opens:

“The meaning of a word—to me—is not as exact as the meaning of a color. Colors and shapes make a more definite statement than words. I write this because such odd things have been done about me with words.”

Perry Miller Adato’s 1976 WNET documentary, Georgia O’Keeffe: Portrait of An Artist—the only video footage the artist ever allowed to be filmed—follows Georgia and her studio assistant, the ceramicist Juan Hamilton, preparing selected prints of her art for press.6 Here Juan delivers one of the funniest, bluntest characterizations of Georgia ever uttered: “She is one of the most lively, energetic human beings I have ever met and that I am sure I will ever meet—and sometimes I think, thank god.” As Georgia smiles knowingly for the camera, the intent of all this work seems clear: She was setting the record straight, however that line appeared to her in her mind’s eye.

Between the 1950s and 1980s, Georgia received a staggering volume of letters from fans—particularly white women, many of whom were housewives and regarded her as an idol, as a friend, as intimate and familiar. The actress Mildred Dorothy Dunnock, quoted in Linda M. Grasso’s sharp, fascinating analysis of these letters, wrote to Georgia: “The first painting I ever saw of yours was in my doctor’s office … [I]t’s there now, on the waiting room wall, a great blue flower, open, limitless, perfect. It is now part of me.”7

Throughout her lifetime, Georgia’s art had continuously been positioned—by her husband, by his circle, and by men who wrote about her work and dominated the critical conversation—as innately expressive of something inherent to women as a category. (Alfred had long championed individual white male artists while collecting and exhibiting white women’s art, art by children, and African art as examples, to his prejudiced mind, of “less intellectualized,” more “primiti[ve]” expressions. Georgia became the ultimate proxy. 8) The frequent, Freudian sexualization of Georgia’s flowers—specifically in her lifetime and by male critics—is an example of this positioning regurgitated by other men (and likely the reason she so pointedly refuted the interpretation). The critic Henry McBride, incredibly, then wrote of her 1926 exhibition: “I like her stuff … but I do not feel the occult element in them that all the ladies insist is there. There were more feminine shrieks and screams in the vicinity of O’Keeffe’s [sic] works this year than ever before.”9 (My brother in Christ, you put the occult element there!)

Perhaps Georgia’s reaction to her literary meme-ification as the mood of the summer would be the same as her response to her fan mail in 1977: “Why do all these people care about me?”10

In April, the artist Jason Garcia, also known as Okuu Pín, of the Santa Clara Pueblo posted another excerpted musing of Georgia’s to Instagram: “It is my private mountain … God told me if I painted it enough, I could have it.”

The mountain, which Garcia addresses as Tsí Pín, is often referred to by its Spanish name: Cerro Pedernal, or Pedernal. Garcia asked his followers, via Instagram stories, for their thoughts and feelings in response to the statement, which he then posted over a clip from the Perry Miller Adato’s documentary. In it, Georgia’s emphasis (italicized below) is clear:

“When I got to New Mexico, that was mine. As soon as I saw it, that was my country. I had never seen anything like it before, but it fitted to me exactly…”

She chuckles as the comments roll past her: “Ghost Ranch is built near my Pueblo—this quote dismisses all the bloodshed that happened,” “O’Keeffe whitewashing the New Mexican landscape. No one can own the land,” and “Manifest destiny much?”

These responses will be part of an exhibit at the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum this fall, TEWA NANGEH/TEWA COUNTRY, for which Garcia is gathering Tewa artists, scholars, and community members to “[question] the Tewa absence from this conception of the landscape and the broader settler colonial context of northern New Mexico.”11

Northern New Mexico has been violently misdescribed as “[Georgia’s] native land”—albeit in the broader consideration of New Mexico as the United States, but Georgia was native to neither—in writing published as recently as 2019.12 The use of “O’Keeffe Country” in reference to the area surrounding and including the village of Abiquiú persists even as the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum has begun to actively discourage its use.13

This is the way the story ends: Georgia O’Keeffe, whose desire for a mountain, for a whole region, tried to swallow its history. But it’s only the end of her story.

Georgia O’Keeffe has been dead for nearly forty years, but her ghost lives on: Mona Lisa smile in a gaucho hat, mascot of “American” modernism, mid-century minimalism, rugged individualism, Western exceptionalism, manifest destiny, the New Woman14, women’s liberation, commodified third-wave feminism (think Queer Eye’s Anthony Porowski’s “Frida Georgia Yayoi Artemisia Louise” t-shirt15, think tote bags and enamel pins), queer community within the orbit of the Taos Society of Artists, girlbossery writ large, gentrification, colonialism, etc. That’s a lot of hats to wear, but as David Bowie’s Nikola Tesla delivers in The Prestige—a movie that deals in the science fiction of cloning and is in many ways about the psychological toll of maintaining many selves and the darker implications of desires at scale (Stay with me!)—“They are all your hats.”

They are all her hats—and some of them ours, maybe yours—to wear, to lift, to examine, even if only to hurl through the open window, to yell out, “ENOUGH of that woman!” There are living artists to support, to engage with; there are more urgent, worthier matters for our limited attention. And it is not everyone’s responsibility to deal with this artist’s sprawling legacy. Nor is it anyone’s specific duty beyond the self-implicated, but there are aspects in which you may be compelled or culpable—hats you may have donned—by virtue of interest or identity. Perhaps you have engaged with one of these emblematic Georgia O’Keeffes in your own art, writing, or reading. Perhaps you have one of her paintings in your home. Perhaps you have visited Ghost Ranch and wondered about the woman who haunts it.

There is the legacy and then there is the person. The Georgia O’Keeffe who in 1933 wrote the words that so many found relatable this summer—nearly a century later—had not yet realized this legacy. A person lives through time and helps build whatever legacy lives across it by their choices and what can be recorded (if time and others keep it). In 1933, Georgia owned no property in New Mexico and had not yet laid ludicrous claims upon a sacred mountain. She was living in New York, in an apartment in the city or at her husband’s family house in Lake George, visiting new friends in New Mexico, entangled in the joys and frictions of these relationships and in her more fraught marriage, reflecting frankly on the ups and downs of living and the challenges of creating. She could not yet command a semi-truck to Abiquiú to fetch a twenty-four foot painting from her garage (as she would upon completion of Sky above Clouds IV in 1965).16 In fact, that spring she was hospitalized for a nervous breakdown—begetting another perennially viral slice of Georgia’s archive from 1933, a letter to the artist from none other than Frida Kahlo.17 But she was beginning to realize the critical and financial success she could one day hang so many hats upon. The year prior, she had completed the painting that in 2014 would shatter the all-time record for the highest-grossing sale of art by a woman artist, dead or alive, in a $44.4 million bid by Walmart heiress Alice Walton (Jimson Weed/White Flower No. 1, 1932).18 For heaven’s sake, she spent the aforementioned summer recuperating in Bermuda!

I didn’t always find this Georgia O’Keeffe—that is, the many Georgias before, or on the precipice of, becoming Georgia O’Keeffe—more interesting than the curated identity, but I do now. And there are many iterations: Georgia O’Keeffe, pre–New York. Georgia O’Keeffe, the commercial artist in Chicago. Georgia O’Keeffe, the teacher in South Carolina, in Texas. Like many people (particularly white women), I was instantly taken with the images of her living out her success in New Mexico, alone but seemingly never lonely, not questioning what or who the photos may have left out. (Georgia O’Keeffe, the millionaire multi-property owner complaining about taxes!)19 “How Georgia O’Keeffe left her cheating husband for a mountain,” ran The Telegraph in 2016, when I was a graduate student. (And the next year, I published my own piece of the kind of surface travel journalism that enables the lives of Georgia O’Keeffe and other white women to eclipse the true, lived history of a place.20) As a then-closeted queer woman, I was drawn to the histories of women who seemed to intentionally choose to remain alone in life. I was searching for, though I didn’t yet understand, histories of other queer women. (Having grown up evangelical, I ironically pored myself into the study of familiar queer isolation rather than search out or explore queer community.) Instead, I fell down the rabbit hole of Georgia O’Keeffe.

The more I read, the more and less interesting she became to me; all the more relatable (her crushes on new friends, struggles to exist in an often ill body and with anxiety and depression) as well as nauseating (her blatant colonialism as well as long-held fatphobia and unsurprising racial perspectives and blindspots21). And the more complicated my admiration became, the more culpable my continued study seemed in her overexposed legacy and her continued spotlight, to the point that I often considered hurling my own hat out the window altogether.

In a life spanning nearly a century, beginning on a dairy farm as one of seven siblings and ending on a pedestal of success—one that left behind a physical archive documenting nearly 70 years of artistic expression and intimate thought—there will be plenty to appreciate, inspire, repel, infuriate, and outright bore. I have no interest in adding more smoothed-over abstractions to the canon of Georgia O’Keeffe for the sake of anyone’s comfort, but I also do not consider any criticism I may levy an indictment of the art itself. (I’m uninterested and unqualified in making those claims!) Such a legacy, preserved, is simply too powerful a lens through which to examine how it came to be—how Georgia became Georgia O’Keeffe—and how some of us came to care so much.

It is in some ways a predictable story about the accumulation of wealth, power, and privilege. (And would she object to my telling it that way? Almost certainly!) But reading the archive of Georgia’s life and her legacy gives us a window into decades of history, culture, and influence—both in the years she lived and in the years her ghost has lived on since. And after nearly ten years of my own reading, research, and deconstruction, I find that I still cannot look away.

This is an invitation to look with me.

Roberta Smith, “Georgia O’Keeffe: Stylist and Curator of Her Own Myth,” The New York Times, March 2, 2017.

Joan Didion, “Georgia O’Keeffe,” 1976, published in The White Album.

Sarah Greenough, My Faraway One: Selected Letters of Georgia O'Keeffe and Alfred Stieglitz: Volume One, 1915-1933, 2011.

Dorothy Norman.

Sarah Greenough (see note #2).

Perry Miller Adato, Georgia O’Keeffe: Portrait of An Artist, WNET, 1976.

Linda M. Grasso, “‘You are no stranger to me’: Georgia O’Keeffe’s Fan Mail”, 2013, Reception: Texts, Readers, Audiences, History, Volume 5, 2013, pp. 24-40, Penn State University Press. Accessed via Project Muse.

Sarah Greenough (see note #2).

Carolyn Burke, Foursome: Alfred Stieglitz, Georgia O'Keeffe, Paul Strand, Rebecca Salsbury, 2019.

Linda M. Grasso (see note #4).

J.Garcia–Okuu Pín Studio (Instagram), April 26, 2024.

Carolyn Burke (see note #6).

Dr. Corrine Sanchez, Dr. Christina M. Castro, and Jason Garcia, “This is Not O’Keeffe Country” (panel discussion), The Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, September 14, 2020.

Linda M. Grasso, Equal under the Sky: Georgia O’Keeffe and Twentieth-Century Feminism, University of New Mexico Press, 2019.

Georgia O’Keeffe, Georgia O’Keeffe, The Viking Press, 1976.

Maria Popova, “26-Year-Old Frida Kahlo’s Compassionate Letter to 46-Year-Old Georgia O’Keeffe,” The Marginalian.

Sarah Cascone, “Alice Walton’s Crystal Bridges Museum Bought Georgia O’Keeffe Painting for Record $44 Million,” Artnet, February 9, 2015.

Barbara Buhler Lynes and Ann Paden (editors), Maria Chabot – Georgia O'Keeffe: Correspondence, 1941–1949, University of New Mexico Press, 2003.

Missy J. Kennedy, “New Mexico's Ghost Ranch Offers Wild Beauty Tamed Long Ago by a Boston Brahmin,” The Boston Globe, September 3, 2017.

Sarah Greenough (see note #2).

I read this in 2 sittings and am officially OBSESSED. This is so so good, Missy. I feel like I just read the first chapter of a glossy new book. More more more please!!!

I desperately want the nickname Angelic Water Moccasin. Loved the details of this so much!