Joan Didion had a type. It was a cutout, which few men and fewer others could pass through, in the shape of the cowboy-costumed silhouette of John Wayne. Tough, decisive, self-assured. Good health, good looks. Strong, sturdy stuff. Humble, no-nonsense origins—nothing and everything to suggest the individual who later emerged, fully formed and seemingly without a past. And “into this perfect mold,” Joan wrote of John Wayne, “might be poured the inarticulate longings of a nation wondering at just what pass the trail had been lost.”1

Like John Wayne, the women who passed Joan’s muster spoke to a past real or imagined. In the contemporary feminism—the (white, middle-class) women’s movement Joan profiled in 1972—she saw an aggrandized self-victimization, writing of the “dolorous phantasm” of the new “imagined Everywoman,” who was “raped on every date, raped by her husband, and raped finally on the abortionist’s table.” Yes, “many women are victims of condescension and exploitation and sex-role stereotyping,” she wrote, but “nobody forces women to buy the package.”2

Don’t complain about the hand you’ve been dealt—play the game and win. And those who did, to Joan, were pioneer women.

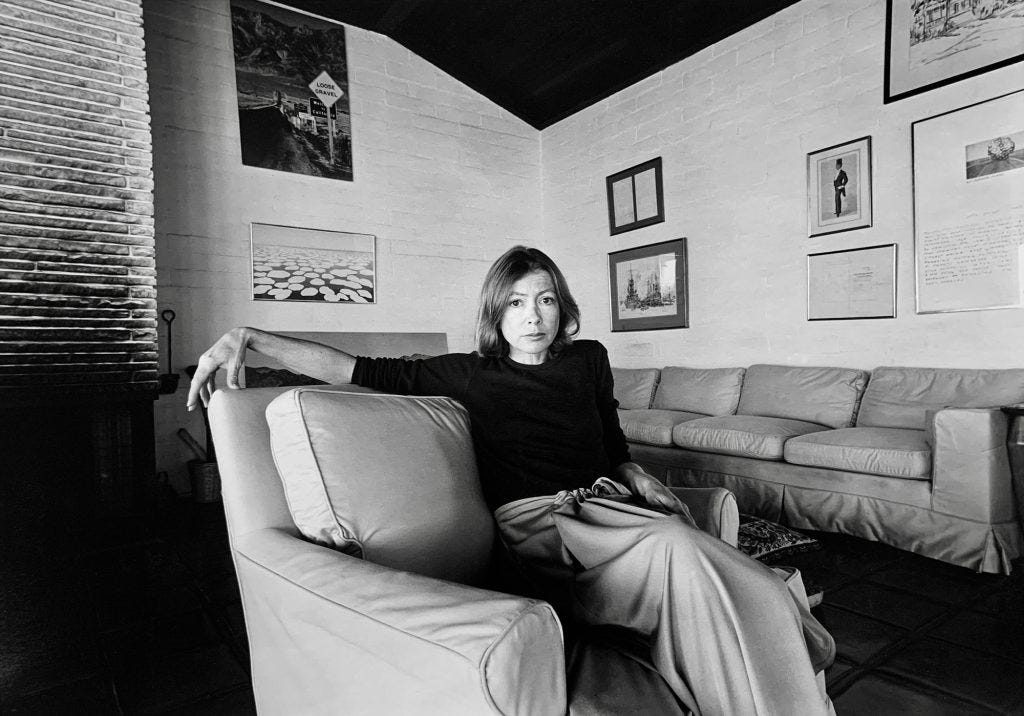

Joan saw in her pioneer women what she prized most in herself. Recounting for The Year of Magical Thinking the sudden death of her husband to a heart attack at their dinner table, she told us how the attending social worker called her a “cool customer,” repeating it like an absurd (but true) mantra. In 2024’s delicious Didion & Babitz, Lili Anolik points out her emphasis on this observation, that she quoted it “ironically, but not really. Really, quoted it sentimentally. She was taken with the description. It’s how she saw herself. How she wanted to be seen.”3 After all, she came from people who had truly—and successfully—crossed the trail. As she often reminded us, her ancestors travelled with the Donner Party but parted ways as the ill-fated group took the newly claimed shortcut that would snow them in that fateful winter; sensibly, her kin stuck to the path already forged.4

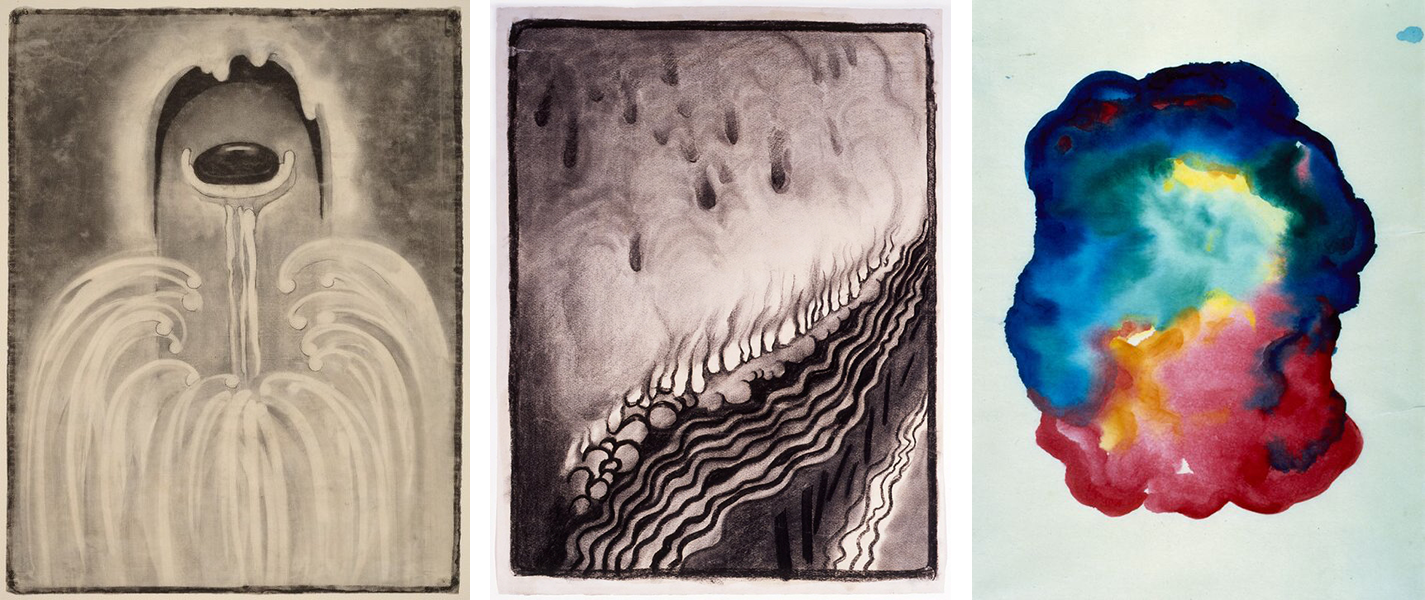

In 1973, Joan Didion and her daughter stood in an airy stairwell before Georgia O’Keeffe’s twenty-four-foot-wide Sky above Clouds IV. Just four years earlier (and just two essays back in The White Album), she had ridiculed the idea, circulating then in Ms. magazine, of critically examining the gendered themes of fairy tales with one’s children. Now, she proudly employed her daughter’s instinctive prodding at ideas of authorship in the lede of her essay on the artist. The child had asked who made the painting. When told, she replied, “I need to talk to her.”

“My daughter was making, that day in Chicago, an entirely unconscious but quite basic assumption about people and the work they do. She was assuming that the glory she saw in the work reflected a glory in its maker, that the painting was the painter as the poem is the poet, that every choice one made alone—every word chosen or rejected, every brush stroke laid or not laid down—betrayed one’s character. Style is character. It seemed to me that afternoon that I had rarely seen so instinctive an application of this familiar principal, and I recall being pleased not only that my daughter responded to style as character but that it was Georgia O’Keeffe’s particular style to which she responded: this was a hard woman who had imposed her 192 square feet of clouds on Chicago.”5

And this, she told us, is a virtue. When she emphasized, “Style is character,” she returned to an idea she’d first explored in her 1961 Vogue essay, “On Self Respect.” “People with self-respect exhibit a certain toughness, a kind of moral nerve; they display what was once called character, a quality which, although approved in the abstract, sometimes loses ground to other, more instantly negotiable virtues.”6

In Didion & Babitz, Lili Anolik characterizes Joan’s writing on Georgia O’Keeffe as her “one unequivocally admiring piece on a woman.” In The White Album, it concludes the brief section of Joan’s essays on “Women,” preceded by the derisive “The Women’s Movement” and the almost-but-not-quite piteous “Doris Lessing.” By the time the page flips to “Georgia O’Keeffe,” one is tensed for a fight; instead, Joan’s prose practically swoons. No other essay of hers is more sentimental or romantic, save her tribute to John Wayne. I’d have been half-tempted to Google “Joan Didion bisexual icon?” had I not just read her apparent advice to lesbians—GROW UP!—in “The Women’s Movement.” (I’m paraphrasing—slightly.)

“‘Hardness’ has not been in our century a quality much admired in women, nor in the past twenty years has it even been in official favor for men,” Joan went on about Georgia, letting her readers who happened to be men know that Georgia had out-swaggered them all—sorry! “She is simply hard, a straight-shooter, a woman clean of received wisdom and open to what she sees.” The line wobbled around in my head as I read Didion & Babitz, which quoted Joan’s husband’s 1978 description of his young self as, by contrast, a “receptacle of received wisdom.”

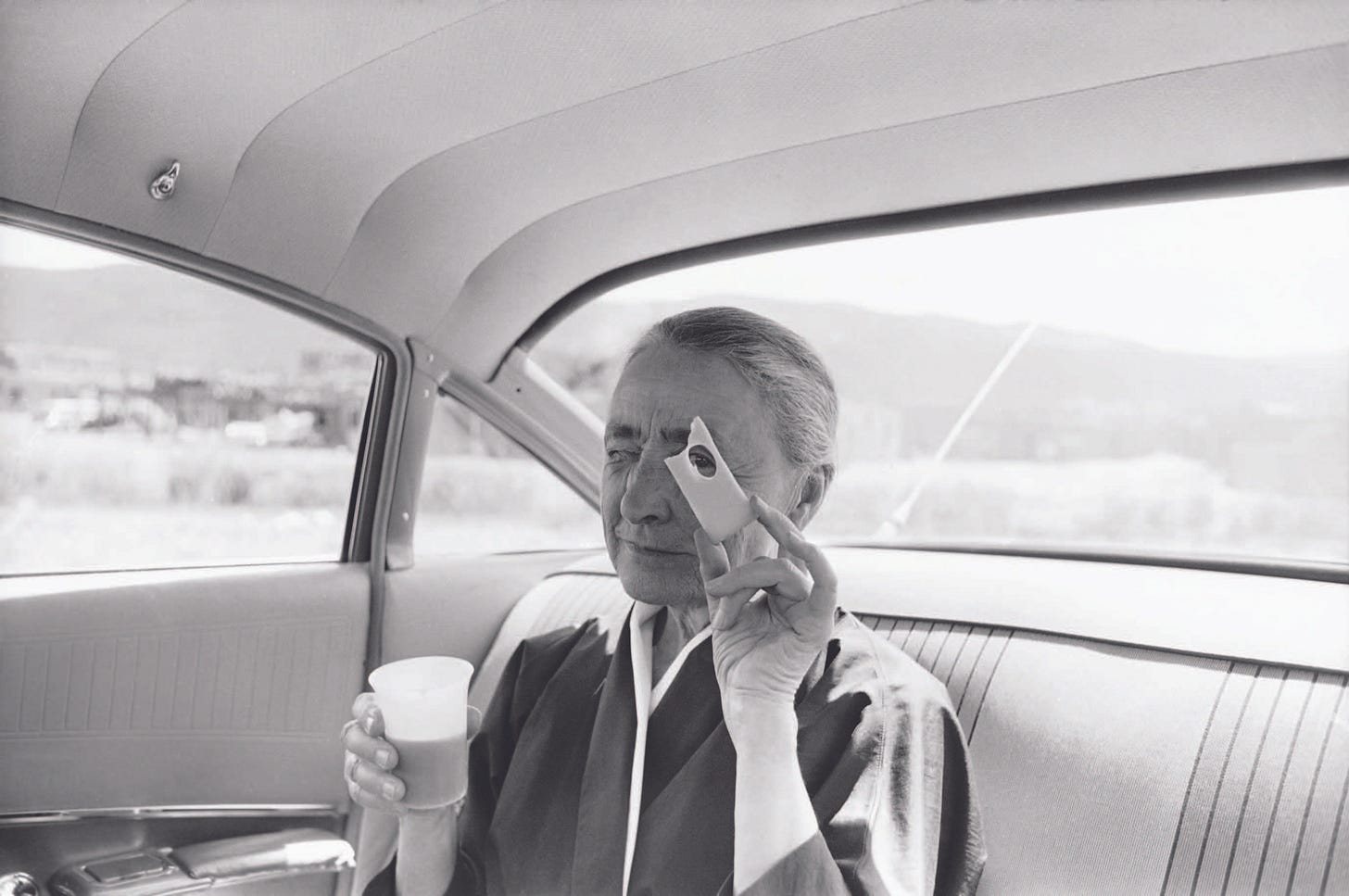

It was not just Sky above Clouds IV that Joan was responding to. The meat of her essay is cut from the text Georgia had written herself for her eponymous, self-curated catalogue, published in 1976 shortly after her eighty-ninth birthday. The book, like Joan’s essay, opens: “Where I was born and where and how I have lived is unimportant.” In the pages that follow, Georgia then went on to tell us her own fairy tale version of where she was from and how and where she had lived.

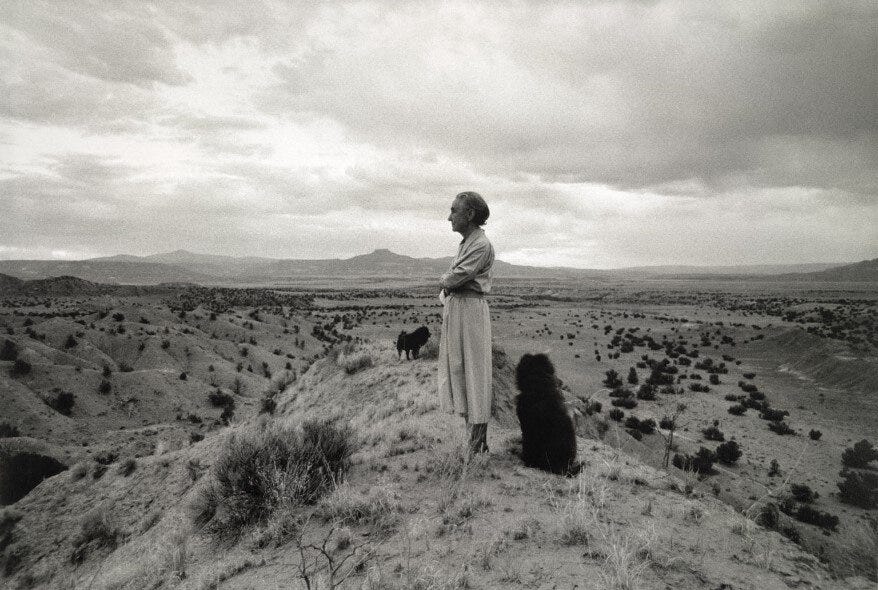

Unimportant? Joan didn’t buy that for one second—to her, where one came from was everything. Footage of Joan collaged into her nephew Griffin Dunne’s 2017 documentary for Netflix (Joan Didion: The Center Will Not Hold) shows the writer pondering: “Don’t you think sometimes people are formed by the landscape they grow up in? It formed everything I ever think, or ever do, or am.” Like Joan more distantly, Georgia descended from Europeans who had traveled across swaths of North America to their new homes, at least partly by actual oxcart. (The various family journeys that converged at Georgia’s birth in Sun Prairie, Wisconsin, are recounted thoroughly in Roxana Robinson’s Georgia O’Keeffe: A Life.) Georgia’s grandmother, Isabella Wyckoff, who made the journey as a child, kept a “tiny” pioneer’s diary, containing an entry that read: “I Came West. April 1854.”7

Born to the previous century, Georgia was, to Joan, a vestige of a past that was fast-fading, was perhaps already gone, a last link to a tougher breed of women like those from her own family: “These women in my family would seem to have been pragmatic and in their deepest instincts clinically radical, given to breaking clean with everyone and everything they knew. […] The past could be jettisoned, children buried, and parents left behind, but seeds got carried.”8

Breaking clean. Clean of received wisdom. Joan would have recognized this “pioneer” logic in more than a few pieces of the narrative Georgia gave the world in 1976: her upbringing on a dairy farm in Sun Prairie, Wisconsin; her teenage and young adult years punctuated by the need to uproot herself perennially to new places for school and work; her mid-career move West from New York to New Mexico; and, most important to Georgia, the retold story of her singular artistic genesis.

“It was in the fall of 1915 that I first had the idea that what I had been taught was of little value to me except for the use of my materials as a language—charcoal, pencil, pen and ink, watercolor, pastel, and oil. […] I decided to start anew—to strip away what I had been taught—to accept as true my own thinking. […] I began with charcoal and paper and decided not to use any color until it was impossible to do what I wanted to do in black and white. I believe it was June before I needed blue.”9

To strip away what I had been taught. It’s not the unfiltered truth, but, as anyone who has sat across the table from a reminiscing aging person knows, it’s not exactly a lie either. It’s the hardening of harder truths into simpler stories. (“We tell ourselves stories in order to live,” Joan wrote.10) Georgia’s letters from 1915, to art school friend Anita Pollitzer, reveal these hard strokes to be far shakier: “I made a crazy thing last week—charcoal—somewhat like myself—like I was feeling—keenly alive—but not much point to it at all—Something wonderful about it all—but it looks lost—I am lost, you know.”11 The true story is far less Promethean, too. In the same letter, she references Picasso and a painting by John Marin. And as biographer Benita Eisler points out in the introduction to the letters between Georgia and Anita, the women frequently and passionately discussed other art, books, ideas, and influences—effectively, if informally, continuing one another’s education. (“In the nineteenth century—still not far from the America of 1916—women’s friendship had been an instrument of self-education,” Eisler writes.12)

The stylistically skeptical Joan bought the simpler (and, notably, peerless) pioneer version as if Georgia had passed it down to her with her recipe for cornbread—partly, perhaps, out of respect or a rare kind of reverence. She had been primed to proselytize this tale by Georgia’s own hand in leading the press. While Joan tried to make sense of the 70s in her notebooks, Georgia had already lived nearly nine decades of a very full life that ultimately, improbably, led her West—where at the end of the trail she outlived and eclipsed her powerful husband and opened her fan mail. (Alfred Stieglitz is no household name!) Georgia confirmed things that Joan had sensed to be true for many years—about the grit and perseverance of certain women—things she worried were changing, disappearing even.

Not many women came along who made Joan feel like that.

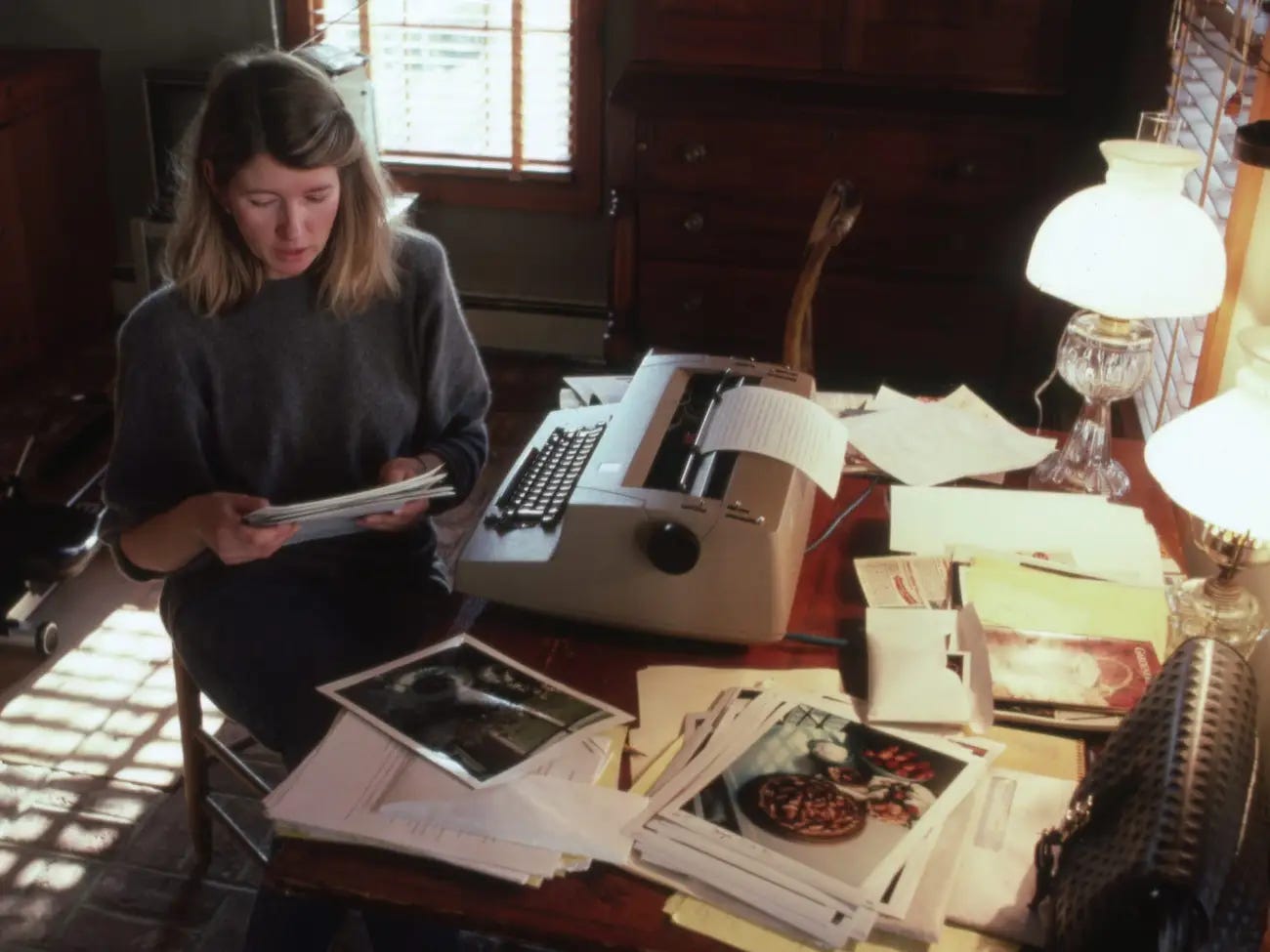

Less than ten years after Joan Didion’s tribute, Georgia O’Keeffe died—a bright star to guide the trail ahead, gone dark. Then, at the turn of a new millennium, Joan booted up a computer, sat down, and typed:

“This is not a story about a woman who made the best of traditional skills. This is a story about a woman who did her own IPO. This is the ‘woman’s pluck’ story, the dust-bowl story, the burying-your-child-on-the-trail story, the I-will-never-go-hungry-again story, the Mildred Pierce story, the story about how the sheer nerve of even professionally unskilled women can prevail, show the men; the story that has historically encouraged women in this country, even as it has threatened men.”13

This was Joan in the year 2000, who did not yet know the double-sided grief—of losing her husband and daughter less than three years apart—that new and old readers would come to know her for through The Year of Magical Thinking and Blue Nights. This was Joan trolling the internet and stumbling curiously onto the early phenomenon of fan sites, digging up the pioneer woman from her unmarked grave beside the trail to animate a new but not unlikely subject: Martha Stewart.

The “women’s pluck” story, the dust-bowl story, the burying-your-child-on-the-trail story, the I-will-never-go-hungry-again story, continues and concludes:

“The dreams and the fears into which Martha Stewart taps are not of ‘feminine’ domesticity but of female power, of the woman who sits down at the table with the men and, still in her apron, walks away with the chips.”14

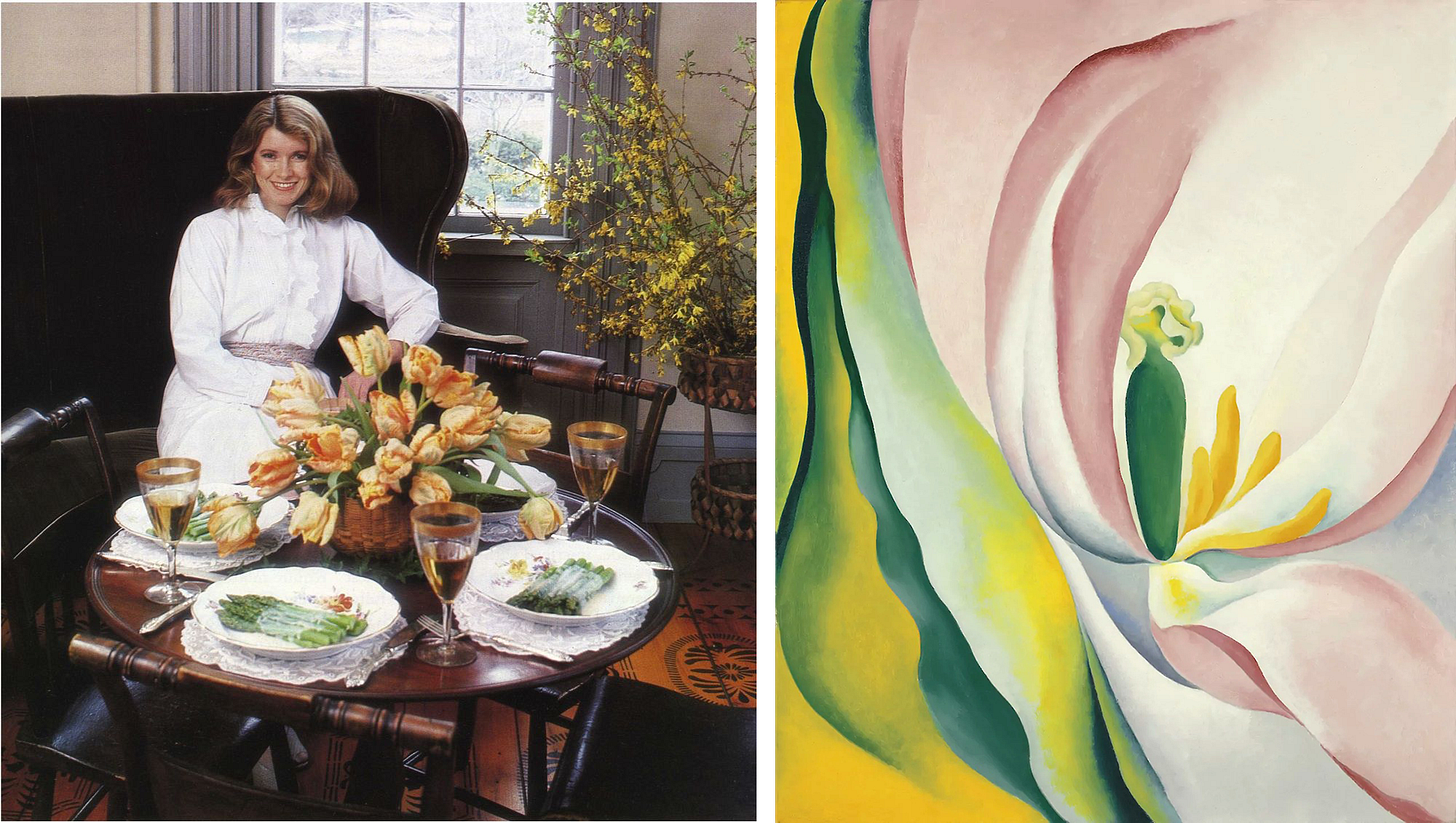

Joan’s words—from an essay titled “Everywoman.com” and published in The New Yorker—are read throughout the 2024 Netflix documentary Martha, to Martha’s measured approval (calling it “a very astute essay”). The essay is perhaps Joan’s second “unequivocally admiring piece on a woman,”15 to return to Lili Anolik’s characterization. For Georgia, Joan painted a brief but heroic fairytale of a hard, remarkable woman; for Martha, Joan took up her sword and slashed point-by-point through Martha’s critics, who then included anonymous website users, unauthorized biographer Jerry Oppenheimer, and the general and ungenerous milieu of the press coverage and talk show interrogations sampled throughout the documentary. These criticisms orbited around Martha’s alleged perfectionism, ruthlessness, and temper. (Martha would not be indicted until 2003, the year Joan’s husband died.) Joan qualified these allegations as so many “insignificant immaturities and economies,” insufficient evidence of true “character flaws.”

If Joan recalled the “Everywoman” she once chided in her essay on the women’s movement, Martha had clearly restored something of Joan’s faith in her.

Like Georgia, Martha’s upbringing fit Joan’s pioneer typology to the letter: the second of six children (Georgia, the second of seven) born to working-class, no-nonsense parents, working capably alongside (and outshining) her siblings in her father’s garden and modeling commercially to help feed her family. She moved from New Jersey to New York for Barnard and then, after marriage, a child, and a stint as a stockbroker, not West—but to Westport. “We were like the original settlers in Westport, Connecticut,” Martha recalls in the documentary.

In Westport, Martha renovated her family’s new old farmhouse—digging gardens, sanding rough wooden floors, and painting the ceiling while listening to radio coverage of the Watergate scandal—and sowed the seeds of her domestic empire. A catering business took root first, a homemade runaway success that gave form to book after book, then a magazine, Martha Stewart Living, then the brand, the IPO: Martha Stewart Living Omnimedia. And behind it all, Martha—the first “self-made” woman billionaire in the country.16

By the time Georgia became a commercially successful artist, she had for years taught visual composition to scores of students and worked as a commercial illustrator on advertisements. Even her core artistic and aesthetic philosophy, to “fill a space in a beautiful way”—influenced by the teachings of American painter, printmaker, photographer, and educator Arthur Wesley Dow, whose philosophies borrowed extensively from the traditions of Japanese woodblock printing—was to approach a canvas more as a designer than as a representational painter.17 The young Martha called upon “the Dutch masters” and her own thoroughly modern sensibilities to arrange her dreamy catering tablescapes. Both women blended fine artistic vision with a shrewd understanding of what the market craved.18

Georgia and Martha shared an affinity for Chow Chows, a distaste for boring people—particularly boring men—and even the anguish of watching their partners of twenty-something years pursue affairs with other, younger women. Neither remarried; both surpassed their former husband’s successes and became household names. These were/are women in possession of character. They were driven, resourceful, and could have continued reinventing themselves forever.

They were also, as Joan characterized of Georgia in her 1976 essay, in possession of “extreme good looks,” “astonishingly aggressive,” and bent on adherence to a certain standard. They were excellent cooks and keepers of fastidious, tasteful homes who wanted things done a certain way. With exacting vision came temper.

Spending part of each of her New Mexico years in her home in the village of Abiquiú—which employed and depended on the labor of dozens of Abequeños over the years—Georgia had her way within her own sphere of home and often, too, in the sphere of the village.19 (When Eve Babitz’s godfather, Igor Stravinsky, took her to New Mexico to meet the famous artist, a young Abequeño sat on the ground rubbing Georgia’s feet.20) The poet C. S. Merrill, who helped catalog and organize the artist’s library in 1973 (which did not include any of Joan Didion’s books on its shelves), sometimes encountered a “crabby scorpion” (Georgia may have, in fact, been a triple Scorpio and was by this point 86 years old): “When she tosses off her little abuses, I find myself keeping empty by repeating a mantra.”21

Martha revisits these kinds of criticisms as levied at Martha (and deftly minimized by Joan): “People felt abused by her.” “She got such wrong ideas about success.” “She was ruthless. In the business world, that’s a great trait for a man.”

Joan’s essays and Martha interrogate why we don’t praise women for the hardness, as Joan described it, or this ruthlessness that we have historically admired or at least accepted in men. (These texts do not more closely examine who, exactly, has admired or accepted such behavior and who has not.) They invite us to reflect on the higher, double standards to which women are still most certainly held. To be sure, Martha was abjectly and unfairly criticized for the apparent sin of daring to take herself seriously, to have such high standards for her work and her company, to not slap on an over-the-top friendly face on TV, to take domestic enterprise to scale. But I wince at her on-camera treatment of an employee: “What knife are you using to cut those? Well, isn’t that a stupid knife? Why? Why, why would you use a little knife to cut a big orange?” And I rolled my eyes when she lamented in 2023 that “America will go down the drain if people don’t return to office.”22

I have humored Joan Didion for long enough. We must now confront the pioneer woman in her full zombie fury and then, having dispensed with her, bury her back beside the trail and leave her behind us at last—for good.

By 1972, Eve Babitz had certainly had enough of Joan Didion’s pioneer drag, drafting, revising, but ultimately not gathering the nerve to send the following:

“Just think, Joan, if you were five feet eleven and wrote like you do and stuff—people’d judge you differently and your work, they’d invent reasons […] Could you write what you write if you weren’t so tiny, Joan? Would you be allowed to if you weren’t physically so unthreatening? […] And you yourself keep making it more all right because you are always referring to your size. And what you do, Joan, is live in the pioneer days, a brave survivor of the Donner Pass, putting up the preserves and down the women’s movement…”23

What makes a pioneer woman? On the near-absurdist stage set by Joan, across which John Wayne strides endlessly on horseback like the rising and setting sun himself, a pioneer is a thin, white woman. (As Eve pointed out, Joan frequently reminded readers of her small size.24) A pioneer comes from a humble past, but that past does not entrap her. She is not a “victim.” She can forget the past, start up again wherever, whenever, and reinvent herself—no matter the cost.

Joan’s pioneer women are rich. Yet the pioneer woman is haunted by scarcity. She “will never go hungry again.” Scarcity breeds a kind of resourcefulness but also, generally, does not encourage many of our other better virtues to take root. Times of scarcity, like recessions, can exacerbate racist perceptions and contribute to greater racial inequalities.25 The perception of scarcity is used to divide workers and classes. Scarcity encourages the hoarding of wealth and power and permits behaviors that prioritize individual prosperity over collective gain.

No one makes a million dollars—and certainly not a billion—by the sweat of their own brow.26 Georgia and Martha were undeniably the architects behind their own successes, but the labor of others enables the rapid accumulation of such vast wealth. Is there no obligation here for (white) women to be “nice” or—please, let’s be specific with our words—kind, fair, or at the very least, accountable?

A past of scarcity permits Joan’s pioneer women to be a little “crusty,” though Joan specifically insisted that Georgia wasn’t. A little old-fashioned, a little hard, a little selfish, a little mean. (“Let’s get you to bed, grandma!”) We certainly don’t need to expect or exact thoroughly contemporary lexicons and radical politics from everyone born to previous generations. Nor do we have to throw ours out the window when rushing to their defense. But to Joan, to criticize that valuable hardness, in any of its forms or expressions, in 1976 and even in 2000 may have seemed far too risky a move in the game with the men—with the fate of the easily influenced “Everywoman” at stake. But who was seated at the table with the men to begin with? Joan’s pioneer mythology only grants permission to women (white, thin, perceived straight) who could have gotten away with bad behavior anyway.

The pioneer analogy is apt in a way that Joan does not seem to intend or at least to intend foremost—the exploitative violence enabling the lonesome frontier, the rags-to-riches pioneer success story. And one forges ahead on a far less simple, more readily implicating path when they become, say, a major employer of a small village or CEO of a billion-dollar corporation. Where Joan’s pioneer mythology becomes problematic is in imposing that terrible rightness of necessity—like pushing ahead on the trail would have seemed—every move these women have made is now reborn from it, even if the pasts they’ve outrun are far behind.

In Martha, I see someone who has quite likely reflected on her past, even if she holds a certain “crustiness” about remote work on the whole. Like Georgia when Didion wrote about the artist, Martha is now in her eighties. The world looks very different today than it did in the 1940s and 50s of her childhood in Nutley, New Jersey, the New York of the 60s when she handily mastered what was gatekept as men’s work on Wall Street, and in the 80s and 90s when she showed the nation how to handily—and artfully—master what was thought to be women’s work. And, in turn, I hope that we would have treated her trial and incarceration more kindly today than we did in the early 2000s. For her part, she has handily mastered the present moment, too—she has a podcast, an Amazon storefront, and even seems to run her own Instagram account with a casual ease and humor.27

In other words, she has moved on.

I’ve started using affiliate links through Bookshop.org wherever possible in my footnotes. This means that if you are compelled to purchase one of the many O’Keeffe biographies or letter collections or other books I reference through the Bookshop link in my references section, I will make 10% of the cover price. (If you are interested in reading an O’Keeffe biography but don’t know where to begin, I’d be happy to recommend one or a few based on what you’re most interested in.) If the books I reference are not available through Bookshop, I’ll link to ThriftBooks (but never Amazon).

I fell behind a month, so I’ll be back in April. Thanks for reading and subscribing. ☺

Joan Didion, “John Wayne: A Love Song” (1965), Slouching Toward Bethlehem, 1968.

Joan Didion, “The Women’s Movement” (1972), The White Album, 1979.

Lili Anolik, Didion & Babbitz, 2024.

Joan recounted this family history in most detail in Where I Was From (2003).

Joan Didion, “Georgia O’Keeffe” (1976), The White Album, 1979.

“On Self-Respect: Joan Didion’s 1961 Essay from the Pages of Vogue,” Vogue, republished after her death on December 23, 2023.

Roxana Robinson, Georgia O’Keeffe: A Life, 1989.

Joan Didion (see note #4).

Georgia O’Keeffe, Georgia O’Keeffe, The Viking Press, 1976.

Joan Didion, “The White Album” (1968–1978), The White Album, 1972.

Clive Giboire, Lovingly, Georgia: The Complete Correspondence of Georgia O'Keeffe & Anita Pollitzer, 1990.

Ibid.

Joan Didion, “Everywoman.com” (2000), Let Me Tell You What I Mean, 2021. (Originally published in The New Yorker.)

Ibid.

Lili Anolik (see note #3).

R. J. Cutler, Martha, Netflix, 2024.

Calvin Tomkins, “Georgia O’Keeffe’s Vision,” The New Yorker, February 25, 1974.

R. J. Cutler (see note #16).

Lesley Poling-Kempes, Valley of Shining Stone: Abiquiu, 1997.

Lili Anolik (see note #3).

C. S. Merrill, Weekends with O’Keeffe, 2010.

Samantha Delouya, “Martha Stewart says America will ‘go down the drain’ if people don’t return to office,” CNN, June 7, 2023.

Lili Anolik (see note #3).

For example, she wrote in the preface to Slouching Toward Bethlehem (1968): “My only advantage as a reporter is that I am so physically small, so temperamentally unobtrusive, and so neurotically inarticulate that people tend to forget that my presence runs counter to their best interests.”

Amy R. Krosch & David M. Amodio, “Economic scarcity alters the perception of race,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 111(25):9079–9084, June 9, 2014.

When Georgia O’Keeffe died in 1986, her net worth was estimated at about $65 million. At federal minimum wage (then $3.35 per hour), you would have had to work 19,402,985 hours (more than 2,000 years) to earn that yourself. In 1999, Martha Stewart’s net worth peaked at more than $1 billion. At the adjusted minimum wage ($5.75 per hour) you would have had to work more than 173,913,043 hours (almost 20,000 years).

Heather Dockray, “The best of Martha Stewart's deeply weird personal Instagram account,” Mashable, May 8, 2019.

The Cult of Joan is bit of a mystery to me. Yes, she writes brilliantly, stylistically, but as far as what she writes about, rather than how, I think she gets away with a lot. Not more than a man, perhaps, but certainly more than other women.

Terrific essay…thank you!

I thoroughly enjoyed your piece Missy. I have been a devoted fan of Georgia O’Keeffe for years and especially since visiting the Ghost Ranch and her home in Abiquiu a few years back. She is one of my two personal icons, the other being Diana Vreeland, who fits the bill of pioneer woman to a “D”.